What is selection bias and how can it damage our decisions?

Brown economics Professor Emily Oster explains selection bias and how it can trick us into drawing flawed conclusions.

Have you ever been annoyed when someone trotted out “evidence” for an argument that felt cherry-picked? Like a friend insisting you should try a new device because they swear by it and know three other people who do too? If so, you’ve been irritated by selection bias. We notice it when advertisers only highlight glowing reviews, or when a colleague shares only the upside of continuing a pet project. But the sneakiest forms of selection bias are the subtlest, and they’re also ones that matter most because they can lead to flawed headlines that change public opinion about everything from screen time to vitamins to how we feed our babies.

This month’s Q&A is a conversation about selection bias with Brown economics professor Emily Oster—one of TIME’s 100 most influential people of 2022 and a bestselling author who’s built a career helping parents separate real evidence from misleading claims. Emily is exceptionally good at explaining how selection bias can trip us up in ways we don’t anticipate, and I hope you’ll enjoy learning more about this pernicious problem from our conversation.

But before we dive into this month’s Q&A, I have an invitation and some recommendations to share…

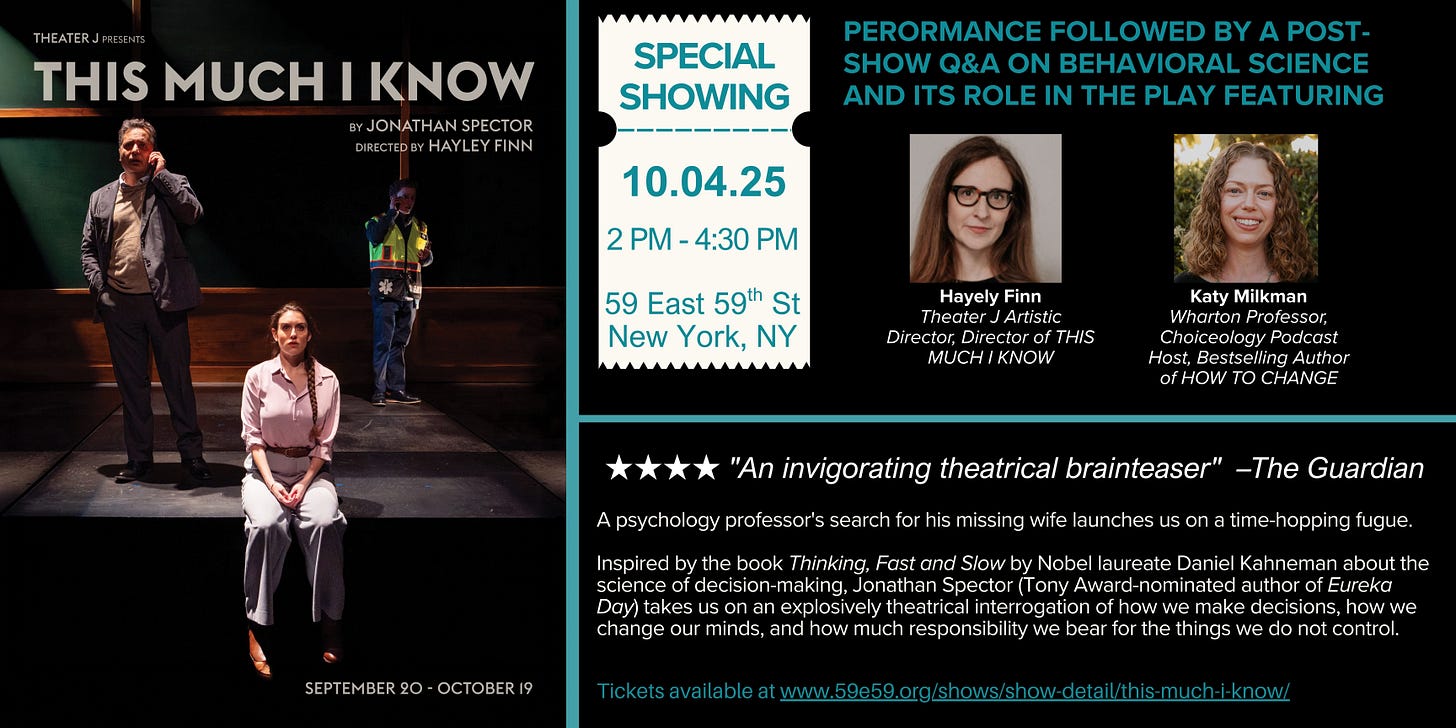

An Invitation: Come See Me Off Broadway in NYC on Saturday, October 4th

Get Your Tickets: Following the 2 pm showing of “This Much I Know,” a play inspired by the book Thinking Fast and Slow by Nobel Laureate Danny Kahneman, I’ll join Director Hayley Finn onstage at 59E59 Theaters for a Q&A about behavioral science and its role in the show.

This Month’s Recommended Listens, Watches and Reads

What Makes Teams Great: A new episode of Choiceology featuring University College London Professor Colin Fisher explains the ingredients that scientists have determined help ensure teams excel.

A 30 Day Challenge to Boost Your Health IQ: My research group at the University of Pennsylvania has teamed up with CNN to share a 30 day online challenge we created to upgrade your health IQ in 60 seconds per day. Are you up to the challenge?

An Inspiring TED Talk: Former Wharton MBA student, fellow Penn professor and past Choiceology guest Dr. David Fajgenbaum shares his incredible story about how nearly dying helped him discover his own cure (and many more).

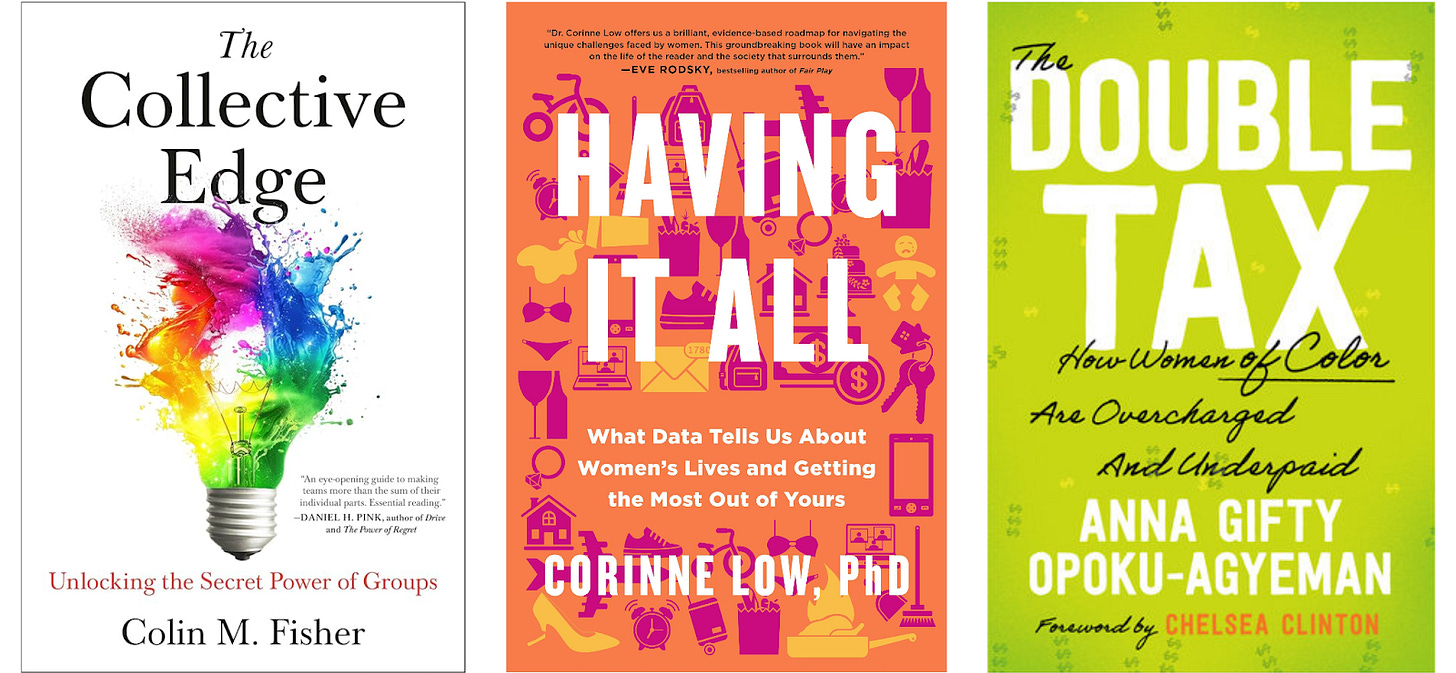

Congratulations to my friends and fellow academics Colin Fisher (author of THE COLLECTIVE EDGE), Corinne Low (author of HAVING IT ALL) and Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman (author of THE DOUBLE TAX) on their new books, pictured below.

Q&A: What Is Selection Bias and How Can It Trip Us Up?

This Q&A from Choiceology is with Brown economics Professor Emily Oster, who was named one of the 100 most influential people in the world by TIME magazine in 2022 and is the best-selling author of numerous books about pregnancy and parenting as well as the CEO of ParentData. Here she discusses selection bias and her research on how this pernicious problem with data can prevent us from making wise decisions.

Me: I want to start really basic. Can you define selection bias?

Emily: Sure. Let's say you were interested in the average height of the population. If you took a bunch of random people and measured them, that would be a good method. But let's say you only selected men. Well, then your heights would be too big for the average because men are on average taller than women. That's a form of selection bias. In this case, we've selected a group that is not representative of the whole population.

Me: I want to try playing a game next if you’re willing.

Emily: Is it poker? I'm so good at that.

Me: It’s not poker. I just made it up and it’s called "Name the Potential Source of Selection Bias in That Claim."

Emily: That sounds like something I would be better at than poker.

Me: Ha! Me too. I'm going to make up some headlines. These aren’t true statements, but they're plausible. And I think you're going to be like, "Here's what I'm concerned about in terms of selection bias" right away.

Emily: All right, I'm ready.

Me: OK, here we go: “A Survey of New Yorker Readers Found that Most Americans Read at Least 10 Books Per Year.”

Emily: Concern: The New Yorker is basically a book. So, you're taking a bunch of people who are already reading books and asking them, "How many books do you read a year?"

Me: “Kids Who Spend More Time in Front of Screens Score Lower on Their SATs.”

Emily: Concern: There’s an education confound. Parental education is highly correlated with screen use, and it’s also correlated with SAT scores.

Me: OK, great. So basically, the kids who are not being allowed much screen time have parents who are better educated?

Emily: Exactly.

Me: “Intermittent Fasting is Great for Your Health.”

Emily: The kinds of people who choose to do intermittent fasting are also doing all kinds of other things that are good for their health, like exercising and eating well when they are eating. They're also more educated, and so they have more resources and more access to medical technology. So that’s responsible for their good health, not the intermittent fasting.

Me: All right. This one is going to feel close to home: “Moms Who Breastfeed have Dramatically Smarter Kids, So You Should Never Feed Your Baby Formula.”

Emily: So, we know for that statement that the confound is largely with education and parental family background. More educated, wealthier moms have more resources and are more likely to breastfeed. Those characteristics are independently associated with child test scores, and it's very hard to separate them out in the kinds of analysis you're talking about.

Me: All right, this is my last one: “Everyone Who Eats Quaker Oats Loves Them.”

Emily: That's amazing because a lot of ads are like this. So, let's say everyone tried Quaker Oats, and half the people liked Quaker Oats and half the people didn't. Well, people who didn't like Quaker Oats, just wouldn’t eat them anymore. And so, then you come back later, and you ask the people, "Do you like Quaker Oats?" But the people who are eating them are the people who like them in the first place. There's such a direct selection problem there.

Me: Thank you for playing my silly game. Now I want to get into some of your research. A lot of the papers you've written are about rooting out sources of selection bias in data to find answers to practically important questions. Could you tell me about a favorite paper on this topic?

Emily: Yeah, my favorite paper is about the dynamics of this process. The leading example is vitamin E. There's a lot of selection with vitamins. If you link them with health, you're concerned that the kinds of people who take vitamins are different from those who don't. I was interested in how that relationship evolves as we tell people different things about the value of these vitamins. In the mid-1990s, people were told that vitamin E was really good for heart health and preventing cancer. The idea was that vitamin E is this magical thing you should be taking a lot of.

And when you look in the data, you can see that, at that time, people who are also doing all kinds of other stuff for their health start taking vitamin E. It's the people who exercise more, the people who don't smoke, people who eat vegetables, people with more education. There's a whole range of things that are predictive of adopting vitamin E when we tell you it's good for you. And as a result, if you look at the link between vitamin E consumption and mortality over time, actually, before we told people it was good for you, there's a little bit of a link. And after we tell people it's good for you, there's a much stronger link. So, if you only look after it's like, "Wow, vitamin E really makes you not die!" Then in 2004, they realized not only is vitamin E not especially good for you, but actually, if you take too much, it can kill you.

So, then there's a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials, which says actually in high doses vitamin E is really bad and in moderate doses it doesn't matter. Then all those people who started taking it before, stopped taking it. And the link with mortality goes back down. So, it's an example, I think, which really problematizes some of these observational studies and just digs into, "What are the actual mechanisms by which this is happening?"

Me: I really love how that research illustrates the problem. When do you feel like our tendency to be naive about selection bias is most problematic for people in their daily lives?

Emily: I think this can become quite problematic when it causes people to make choices that are otherwise very difficult for them or make them upset. Something like breastfeeding, which I write a lot about, where I think we spend a lot of time telling people about benefits of breastfeeding that aren’t supported in the data. Many of the things we say, like that breastfeeding will make your kid smarter, thinner, or healthier later, are just not supported in the best data. Because breastfeeding is hard for a lot of people, and because it doesn't work for a lot of people, and because it can be a source of tremendous shame, I think we should try to move away from telling people things that aren’t supported by data, when they’re going to feel bad about them.

Me: So, like, I feel like I can't go back to work or I spend six hours a day pumping because I believe not breastfeeding will destroy my child’s future. That's costly.

Emily: Or I sink into postpartum depression. Actually, one of the things I heard from a lot of people's spouses was "My partner is really depressed about this. It's not working, and she's killing herself to do this. And she's really sad, and I just think if she could let up the pressure with some better evidence, she would feel better." And I think that's a real cost to people.

Me: What should people do differently in their lives now that they know a little bit more about selection bias?

Emily: The most important thing is don't lurch. When you see new studies about finances, health, or whatever, there’s a strong temptation to change your behavior based on that. Occasionally, some new finding is very believable and reliable, and you should change your behavior. But most findings are not that good. So, don't change what you're doing based on one headline or one study. Try to think about everything together.

Me: That's great advice in general.

Emily: Just take a deep breath.

Me: I love that. Thank you so much for your time today, Emily.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

To learn more about Emily’s work, listen to the episode of Choiceology where we dig into selection bias, check out her website ParentData.org or get a copy of one of her outstanding books EXPECTING BETTER, CRIBSHEET, THE FAMILY FIRM or THE UNEXPECTED.

That’s all for this month’s newsletter. See you in October!

Katy Milkman, PhD

Professor at Wharton, Host of Choiceology, an original podcast from Charles Schwab, and International Bestselling Author of How to Change

P.S. Join my community of ~100,000 followers on social media, where I share ideas, research, and more: LinkedIn / Twitter / Instagram / BlueSky / Threads

Great stuff, as always Dr Milkman. I feel smarter just reading your work. Thank you!

I am not a psychologist or a person who has researched extensively regarding this but I have observed over the period of years that people take almost everything in absolute terms and not with a pinch of salt. People listen to one thing and make that particular notion in their mind that this is what it is, where is psychological flexibility? I will give you an example in training for running, now a days double threshold workouts are considered to be the go to thing for professional athletes to level up and reach their peak performance. Matthew Richtman(American) ran a 2:07:57 for marathon in March this year & it was his only second marathon and he said in his post marathon interview that he didn't ever do any double threshold workouts. Yeah I know there are exceptions to the rules for which Richtman might be the one. But the catch is the people who have started running or have been running for a couple of years start to incorporate double threshold workouts in their training not knowing the professionals doing this have huge aerobic base/engine on which their double threshold workouts thrive. They incorporate and don't see the changes or improvement and then they cuss this doesn't work. They don't have a the full ten thousand view to the last decade of those athletes- the way they trained consistently for a decade, did strength training & mobility workouts day in & day out, have properly nourished their body for how long. They just want to have this magic pill of Double Threshold, we should try not to take anything in absolute terms, everything is dynamic & not static. Even the years of research sometimes have fault in them, Lisa Feldman Barrett keeps on saying how people have gotten wrong about emotions over the last how many years & Ellen Langer says a lot about nothing is same for everyone.