The remarkable effects of asking: "How does that work, exactly?"

If you spend much time around kids, you’ve probably heard the question “how does that work?” a lot. A book called “The Way Things Work” has been one of my son’s most prized possessions for years, thankfully reducing the need for me to explain how household appliances and car parts function. Before becoming a parent, it never occurred to me that I wasn’t terribly aware of the exact mechanics that cause a toilet to flush or a piece of legislation to transition from an idea into law. What most of us learn when we’re asked “how does that work” is that it’s surprisingly hard to say. And that’s the focus of this week’s interview, but with a twist – it turns out that asking for explanations of how things work can lower the temperature in political debates (a tip that feels timely as we approach a contentious American election).

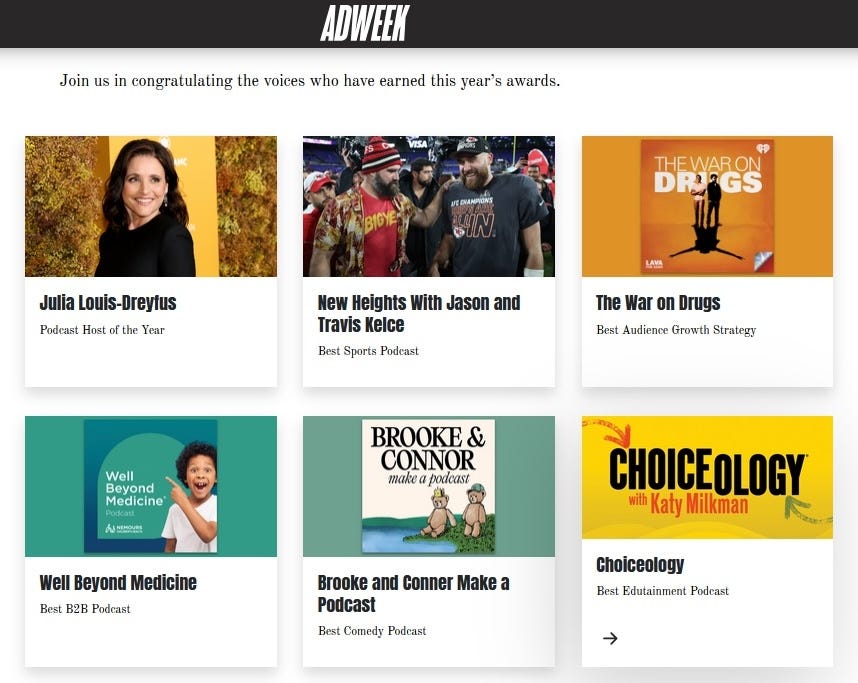

But before we get to that, I do want to share some happy news: Choiceology received multiple awards this summer, which is incredibly gratifying. Thank you to ADWEEK for naming us 2024’s best Edutainment podcast (we were honored alongside superstar podcasters in other categories like Julia Louis-Dreyfuss and the Kelce Brothers).

Thanks also to the members of the Global Association of Applied Behavioral Scientists (GAABS) for voting Choiceology the best behavioral science podcast of 2024. We’re very grateful to our listeners and fans for all of the support! Please keep tuning in, keep referring your friends to the show, and leave us a rating if you haven’t already.

This Month’s Recommended Listens and Reads

The Truth Is Out There: We launched a new season of Choiceology in August, and this recent episode covers Princeton psychologist Taina Lombrozo’s fascinating work on our mind’s preference for simple, single explanations and how it can lead us astray.

How to Kick-Start a Reading Habit: Real Simple offers evidence-based tips, including some sourced from yours truly, on how to get back into reading books after a long hiatus.

The 100 Best Books of the 21st Century: Speaking of starting a reading habit, don’t miss this great reading list from The New York Times Book Review staff.

Mentoring for Good: This short essay shares remembrances of one of my favorite Wharton senior colleagues who passed away last year – the perpetual optimist, Howard Kunreuther.

Q&A: What Happens When We’re Asked to Explain How Things Work

In this Q&A from Choiceology, Brown psychology professor Steve Sloman discusses his research showing that being prompted to explain how something works makes us more humble about our understanding of it and has the potential to reduce political polarization.

Me: Hi Steve, I'm really excited to dive into the illusion of explanatory depth. What is it exactly?

Steve: Well, this illusion is that people think they understand things better than they do. So, this was first demonstrated with simple objects like zippers and ballpoint pens and toilets. You ask people how well they think they understand how they work. And then you ask them to explain how they work. And what you find is that their sense of their own understanding after trying to explain is lower than it was at the beginning. People admit that they don't understand how something works as well as they thought.

Me: That's really fascinating. What drives this bias? Why do we think we understand things deeply until we have to explain them?

Steve: I think the explanation is that we live in a community of knowledge, and we depend on others for much of the information we have. So, the bias is a result of failing to distinguish the knowledge that's in our own heads from the knowledge that's in other people's heads.

Me: Do you have a sense of why I can't distinguish what's in my head from what's in your head, for example? That is, as an expert on decision-making, I think I do actually have a decent handle on the decision-making literature. But why would I think I have a handle on how ballpoint pens or my toilet works and not recognize the distinction?

Steve: Well, I think that in our very specialized world today, we live on credentials and are all evaluating each other all the time. But we evolved in a group environment where it didn't matter whether the knowledge was in our own heads or the heads of our tribe members. So, I think the reason that we fail to make the distinction is because most of the time it's not an important distinction. Most of the time we're collaborating with other people and depending on the knowledge that sits in our tribe. And so, the phenomenon arises simply because we depend on those other people for our decisions and actions.

Me: What can we do to de-bias this illusion? I know you've done some work that shows there are strategies that can help reduce it.

Steve: Well, the first question is do we want to de-bias it?

Me: Good point.

Steve: And most of the time, I'm not sure it matters, but here's a case where it really does. My entree to this illusion was doing work with some colleagues showing that you find exactly the same illusion with political and social policies.

Me: So just to be clear, if you and I are having a conversation about how we're going to upgrade the nation's infrastructure, I would think I know more about how that proposed policy is going to work than I really do.

Steve: Exactly. And so, the problem with that is hubris. When we're talking in the social policy domain, we think we understand things better than we do. And that may explain why we feel so strongly about our positions these days. I think it's actually a partial explanation for political polarization.

So how do you de-bias? You ask people to explain. Most people are going to try to explain and discover that they don't really understand how it works. The attempt to explain punctures our illusion of understanding.

When you're asked to explain, you have to talk about something outside of your own brain. You're not talking about your opinion. You're not talking about why you have the position you have on this policy. Rather you're talking about the policy itself and what its consequences in the world will be. And I believe that externalizing things sort of separates them from you, so you're thinking about them mechanistically, but you also don't have the same investment in being right. So, I think it's a way to achieve compromise.

Me: I'm curious if you think there are other settings where this bias can be pernicious. Where else can we reach a middle ground when the illusion of explanatory depth could otherwise lead us to make big mistakes?

Steve: I mean, any context in which there's the potential for conflict.

I hate to say this, but sometimes when I'm talking to my wife, I think I understand what we're talking about probably better than I do. And if I could come to a more accurate conclusion of my own understanding of her intentions and of what caused the conflict, then I would probably be more forgiving, less sure of myself, and we could have a more productive conversation. I think this is true in many businesses, many committee meetings, many faculty meetings.

One of the basic facts about people is that we are hard to persuade. We take our positions strongly. So, I think that lowering the temperature during conflict in general is a good thing. And, in particular, I think that thinking about things mechanistically rather than thinking about our values makes us less egocentric and lets us have more productive conversations.

Me: Could you walk us through one of your studies on how having people work through their actual understanding can reduce polarization?

Steve: Sure. In our studies, one of the policy issues was whether or not there should be a flat tax on all Americans. And you ask people how well they understand the policy and what its implications would be. And generally, people say, "Oh yeah, I understand it." On a one to seven scale, they'll give a four or five. And then you say, "OK, now explain the policy in as much detail as you possibly can." And then people very quickly come to the realization that they don't understand the policy enough to explain how exactly it's going to manifest out in the real world.

So then we ask them again, "Now, how well do you think you understand the policy?" and their judgments are reliably lower. But the other thing we do is we say, "Has your attitude changed at all? on a scale from ‘I disagree completely with the policy’ to ‘I agree completely with the policy.’” After trying to explain, they’re closer to the midpoint of the scale. Their judgments are less extreme.

Me: That's really encouraging. I learned a lot from this conversation.

Steven Sloman: It was a pleasure.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

To learn more about Steve’s work, listen to the episode of Choiceology where we dig into the illusion of explanatory depth or buy a copy of his fantastic book, The Knowledge Illusion.

That’s all for this month’s newsletter. See you in October!

Katy Milkman, PhD

Professor at Wharton, Host of Choiceology, an original podcast from Charles Schwab, and Bestselling Author of How to Change

P.S. Join my community of ~100,000 followers on social media, where I shares ideas, research, and more: LinkedIn / Twitter / Instagram

No foubt you are doing very nice work for which you are rewarded with awards.Keep up doing it

as I always sdupport it.

You really made me proud for winning prestigious multiple awards this year. I send my deepest

love hugs and Kisses from the core of my heart as I am so much happy!!!