My top book recommendation of 2025 (so far)

“After the Spike” is the most eye-opening book I’ve read this year. Here’s a preview of why.

One of the unexpected joys of being part of the behavioral science and economics community is getting early access to big, bold new ideas—sometimes before they hit bookstore shelves. Occasionally, a book manuscript comes along that’s so thought-provoking and urgent, I can’t stop thinking about it.

And this year, one book really stood out. It’s a book called “After the Spike: Population, Progress, and the Case for People” by two economics professors at the University of Texas at Austin named Dean Spears and Mike Geruso. Here’s what I said in the book endorsement I offered them:

“AFTER THE SPIKE is the most interesting and important book I’ve read in years. Spears and Geruso explain why Earth’s population is headed for collapse if we don’t make dramatic changes, and they do it using rigorous analyses, compelling data, and striking visual evidence. After debunking common myths about why this crisis might not be bad news, they offer thoughtful, research-backed guidance on how humanity can respond. Packed with eye-opening graphs and surprising facts, AFTER THE SPIKE is a must-read for everyone on our soon-to-be lonelier planet.”

Today, After the Spike is officially on sale and available to the world. You may see excerpts in The New York Times or The Atlantic this summer, and while both will be worth a read, I’d strongly encourage you to invest in the whole book. This newsletter is devoted to a Q&A with Mike Geruso, who kindly offered to share his insights with all of you.

Q&A with UT Austin Professor and Economist Mike Geruso (co-author of After the Spike)

Me: First, could you briefly explain the premise of your excellent new book? That is, what is “the spike”, and why are you so sure that we should be concerned about it (and what comes after)?

Mike: Birth rates have been falling everywhere around the world. Not just the rich parts of the world or in a handful of countries in East Asia, but almost everywhere. Two thirds of people today live in a country with a birth rate too low to sustain its population over time—meaning fewer than 2 kids in the next generation to replace 2 adults in the last. Within a few decades, that will be true for the worldwide average. And so the global population will begin to shrink. All of the major institutions that make population projections agree on that future in their centerline projections.

Once the decline begins, it could be very fast. Consider a global average birth rate of 1.5 kids for every 2 adults—which is between the current birth rate in Europe and the current birth rate in the US. In that scenario, the global population would decline by half every 60 years or so. If that is indeed the future we’re heading towards, it would be an unprecedented change with sweeping consequences.

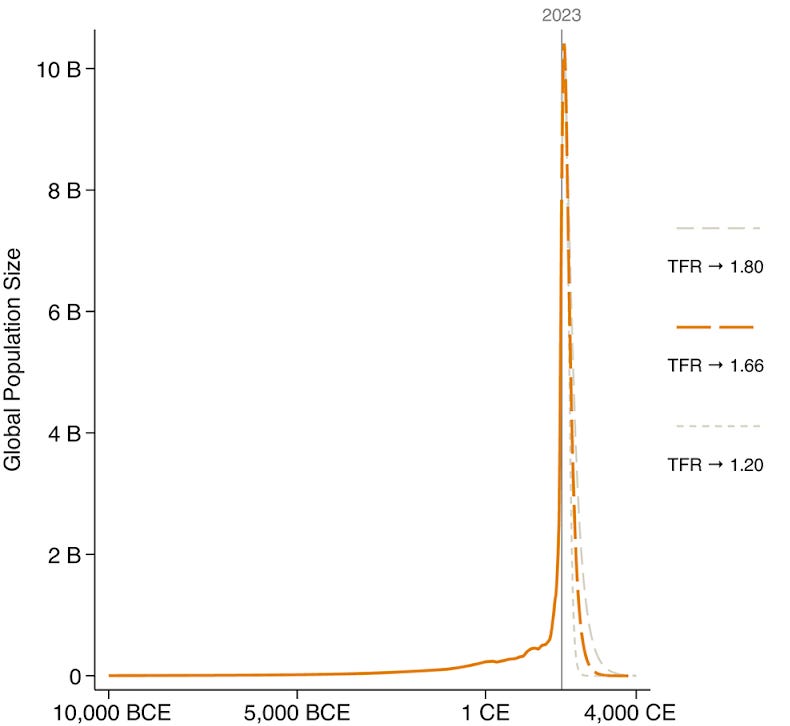

To zoom out and get a sense of just how fast things could change, here’s a plot from a 2024 paper we wrote with Sangita Vyas and Gage Weston. It shows population paths in different scenarios for global fertility. The world wouldn’t need to converge to very low fertility for a big world to be a short blip in history. Anything much below a total fertility rate (TFR) of 2.0 would yield a pretty sharp decline. For reference, a fertility rate of 1.6 is the statistic for the US today. 1.8 is the present average over all of Latin America. 1.2 would be China around 2020; it has fallen since.

In the book, we dive deep on the idea that there are no “automatic stabilizers” that anyone should rely on to kick-in and halt the decline. Even after the world has been shrinking for decades, people could continue to decide that choosing a family size similar to what people choose today works best for them. That means a lot of families with two kids, some with one or none, some with three or more, all averaging out to a total fertility rate below 2. And if they did, the decline would continue decade after decade. So if there is going to be any offramp to global depopulation, it will have to mean that individuals and societies have chosen to make a change. We wrote the book to start a conversation about what sort of future we should all be hoping and working for.

Me: As someone who studies judgment and decision making, I found it fascinating that despite the incredibly compelling data you share that birth rates have been dropping across every culture and continent for as long as we’ve been keeping track, scientists hadn’t fully appreciated the long-run implications of this for our society until quite recently. Could you talk about why so many people overlooked the crash that’s now clearly up ahead?

Mike: Yes, this is super interesting. Depopulation – and especially the fact that so many smart, informed people didn’t see it coming – looks like a case of what judgment and decision-making psychologists call “stock-flow failure.” That term comes from Matthew Cronin and coauthors in a 2009 study. For centuries, the size of the worldwide population has been growing. That’s the stock. But for the same centuries, the global birth rate has been dropping. That’s the inflow. That’s an unintuitive situation because the inflow was declining even as the stock was increasing fast. Meanwhile, it has been the outflow that has been determining rapid population growth: death rates have been falling, especially for children and babies. Kids are more likely to survive to adulthood than before, and that improvement has meant population growth.

But now the inflow (birth rates) has slowed so much that it’s about to cross below the outflow (death rates), causing populations to begin shrinking. In fact, all the way back in 1980, one-fifth of people already lived in a country with a birth rate below two. Europe, Canada, Australia, Japan, and Cuba, for example, all moved below two in the 1970s. So we had some strong signals, even decades ago, that depopulation was the world’s most likely future. But the stock was still rising—so as Cronin and colleagues might predict, that misled us about what was coming next.

Me: I found the evidence you presented that we’re about to see massive global population decline incredibly compelling. But I was even more fascinated by some of the arguments you made about why this is bad. Could you talk about some of the key reasons you think we should be worried, as a society, about exponential population decline (rather than complacent)?

Mike: One reason to not be complacent is to understand that Progress Comes from People (that’s the title of our chapter 6). There’s an old Malthusian idea that more quantity of life means less quality of life. But that’s not what today’s macroeconomists who study growth and progress think. Over time, living standards are improving because new people keep adding to our species-wide, shared stock of know-how, creativity, and understanding.

Once humanity breeds some new sweet apple variety, discovers that soap can reduce infections, develops a statistical technique like ANOVA, or learns to efficiently harness solar power into electricity, others can put those ideas to good use and make lives better. Ideas are an endlessly renewable resource. And not just in high tech. Tailored gene therapies come from human innovation, but so does the technology of how to organize a construction crew or a legislature in a representative democracy. The accumulation of non-rival ideas is the reason why billions of us today can live healthier, safer, longer, richer lives than kings and queens of old. And here’s the key: all of those ideas come from other people. We benefit gorgeously from sharing the planet with many others and getting to live in a time after many others have built the progress that we get to enjoy. We shouldn’t be complacent about upsetting that applecart!

Me: As someone who’s very concerned about global warming and other ways humans are harming planet earth, I was surprised to learn that depopulation is unlikely to stop climate change. Could you explain why environmentalists should not be rooting for depopulation?

Mike: We’re concerned about these issues too. It’s exactly because environmental problems like climate change and habitat loss are so urgent that environmentalists shouldn’t count on population decline to bail us out or offer a reprieve. Once we turn the corner from population growth to population decline—which could be in the 2060s, 2070s, or 2080s, depending on which projection one considers—decline will be fast. But in the meantime, the population will still be growing.

By the time of the 2050 climate goals laid out by the Paris Agreement or the IPCC or the Biden Administration, the global population will be larger than today. That means the only solution to getting a problem like greenhouse gas emissions under control is to actually get per capita greenhouse gas emissions under control. Population decline that starts a few decades from now is just too little and too late to do much good for any urgent environmental challenge. We may succeed or fail in avoiding the worst climate disaster, but that success or failure will depend on policy and technology and individual attention that supports these. Focusing on population is worse than no help. Hoping it may come to the rescue is a distraction from any real solution.

Me: What got you interested in learning and writing about the coming population crash?

Mike: What got us started on writing research papers, op-eds, (and eventually the book) was how compelling the basic facts of population change were. Today there are 8 billion people. But for most of humanity’s hundred-thousand history there were only a few million. So much of the shared prosperity that has swept over the world during the past few hundred years—so much of the material and social progress—happened in the same centuries when the population was growing fast and became large. That is a reason to take seriously the question of what the shape of the world will be when the size of the world becomes so much smaller. Birth rates have been starting to get attention, but most of that attention has been missing this big picture. So we wanted to bring our perspective, grounded in social science, to this issue.

Me: I want to turn to solutions. You write about some of the places in the world that are already dealing with incredibly low birth rates, like Japan and South Korea, as harbingers of what’s to come for the rest of us. What can we learn from the policies that have failed to reverse low birth rates in those societies?

Mike: The biggest lesson from the places where fertility has been low for a long time is that nobody has this under control. Governments—and researchers, for that matter—don’t know how to turn things around. There has been plenty of interest in raising birth rates to replacement levels in South Korea, Japan, Europe, and elsewhere. But in no case has any country succeeded in doing so. Sometimes people think that governments have a lot of power to change this. We dismantle these myths in our book, where we analyze Romania’s policy to ban birth control and abortion (and in the other direction, China’s one child policy). Neither has had the big, durable effects they’re often credited with.

The things that liberal democracies have tried haven’t moved the needle much either. For example, free high-quality universal child care would be a boon to parents, but countries with the strongest pro-parent support don’t have above-replacement birth rates either. Researchers estimate that giving parents cash, setting up quality, affordable daycare, mandating parental leave, and the like have had at most small effects on fertility. The clearest lesson for us is that policy researchers and social scientists are at the very beginning of understanding the social and economic determinants of low fertility and how to reverse it. So a top priority for now should be more investment in research and learning.

Me: If you were given the power of a dictator to solve this problem with any policies you felt would be fair and effective, what would you do?

Mike: I wouldn’t trust anyone to have dictator-like power on any issue, and especially not this one! The question, though, really underscores that a big part of the challenge here is that no one person (or one country or one generation) decides the birth rate. Instead, raising the birth rate would be a positive long-term global externality. This is similar to the way that greenhouse gas emissions are a negative long-term global externality. There is a misalignment of incentives.

Really supporting parents, in proportion to the tremendous social value of children, would mean reforming our economic and social institutions. We don’t know what that looks like, but we do know that it would be a big change from the present, where we ask parents, and particularly mothers, to shoulder a large share of the costs of making the next generation, while the world as a whole benefits from that labor.

Society probably won’t decide to really shift priorities to address this as long as most of us carry around the doomer, Malthusian view that people are bad—for the planet, for one another. So the one thing we most hope for is a new orientation: that we all begin to better understand that the people around us are a source of abundance, not scarcity. That’s a conversation we hope our book starts.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

To learn more, pick up a copy of the book After the Spike wherever books are sold.

That’s all for this month’s newsletter. I’ll be taking the rest of the summer off from Milkman Delivers, but I’ll be back with new interviews in the fall, so stay tuned!

Katy Milkman, PhD

Professor at Wharton, Host of Choiceology, an original podcast from Charles Schwab, and International Bestselling Author of How to Change

P.S. Join my community of ~100,000 followers on social media, where I share ideas, research, and more: LinkedIn / Twitter / Instagram / BlueSky / Threads

I know this sounds kinda under-complex, but I think it still summarizes the essence of what I think is true: capitalism or kids. Either, or. Both won‘t work in the long term.

The question is, what then? We‘ve had indigenous, subsistence-based cultures, we‘ve had mercantilistic ones, we‘ve had communism. None was able to bring some decent prosperity and dignity to more than a few. So, what then? I‘m in favor of experimenting locally, cancelling regulations to do so, evaluate what works, then apply on other places. Sooner rather than later. For being prepared.

No, no, no. Earth's resources are finite. Even our own created resources like housing are also limited (for a variety of reasons). We have only - to use Jospeh Campbell's words - this one 'spaceship' - Earth - to house and support us all. We can't continue increasing our global population because the planet cannot support a consistent increase. All environmental science confirms this. It seems very clear that a declining population is environmentally - for nature, and thus for humans dependant on nature - a good thing!