Do you worry too much about unlikely events?

UCLA Professor Craig Fox explains how we think about low-probability events and how to make better choices in an uncertain world.

I come from a long line of worriers. I worry about getting caught in the rain, so I often lug around an umbrella on sunny days. I worry about my phone dying, so I keep it perpetually charging—and I never leave home without a portable power bank. As a student, I worried so much about failing tests that I over-prepared myself right into a career as a professor.

Some of these worries, while a little excessive, have served me well. But not all worries are innocuous. And many of the most problematic ones come from overestimating how likely something bad is to happen. For instance, overestimating the low risk of a plane crash or a snake bite could keep you from taking perfectly safe flights or enjoying the great outdoors. Overestimating risk could also lead you to unnecessarily pay for pricey insurance on a $40 train ticket or an extended warranty on a cheap toaster.

Right now, in our age of heightened uncertainty, my worries are on hyperdrive. It's easy to panic over every new headline about the terrible things that could happen (but are still very unlikely). To help cooler minds prevail, in this month’s Q&A, I’ve turned to UCLA Professor Craig Fox to explain why our brains tend to overestimate the likelihood of rare events—and what we can do about it.

But first, here’s some information about a Zoom event I’m co-hosting that you might enjoy attending plus a few listens and reads I recommend…

A Zoom Event on 4/30 with Harvard Economist and All-Around Superstar Raj Chetty

There’s widespread consensus that Raj Chetty is among the most extraordinary social scientists on the planet. Among other accolades, he’s received a MacArthur “genius” fellowship, the John Bates Clark medal (given to the economist under 40 whose work is judged to have made the most significant contribution to the field), and Harvard’s George Ledlie prize (awarded for research that made the most valuable contribution to science, or in any way for the benefit of mankind).

On 4/30 from 12 pm - 1 pm ET, I’ll be moderating a Zoom event where Raj shares his latest research on “The Science of Economic Opportunity: New Insights from Big Data” and takes questions. Anyone and everyone is welcome to join the event. All you have to do is register here: tinyurl.com/chetty430

This Month’s Recommended Listens and Reads

The Reality Trap: A new episode of Choiceology featuring Harvard Professor Julia Minson explains naïve realism, which is our tendency to presume our perception reflects the objective truth and that those who see things differently must be wrong.

The University President Willing to Fight: This episode of The Daily podcast features an interview with Princeton President Chris Eisgruber who eloquently articulates the imperative to protect academic freedom (making me very proud of my alma mater).

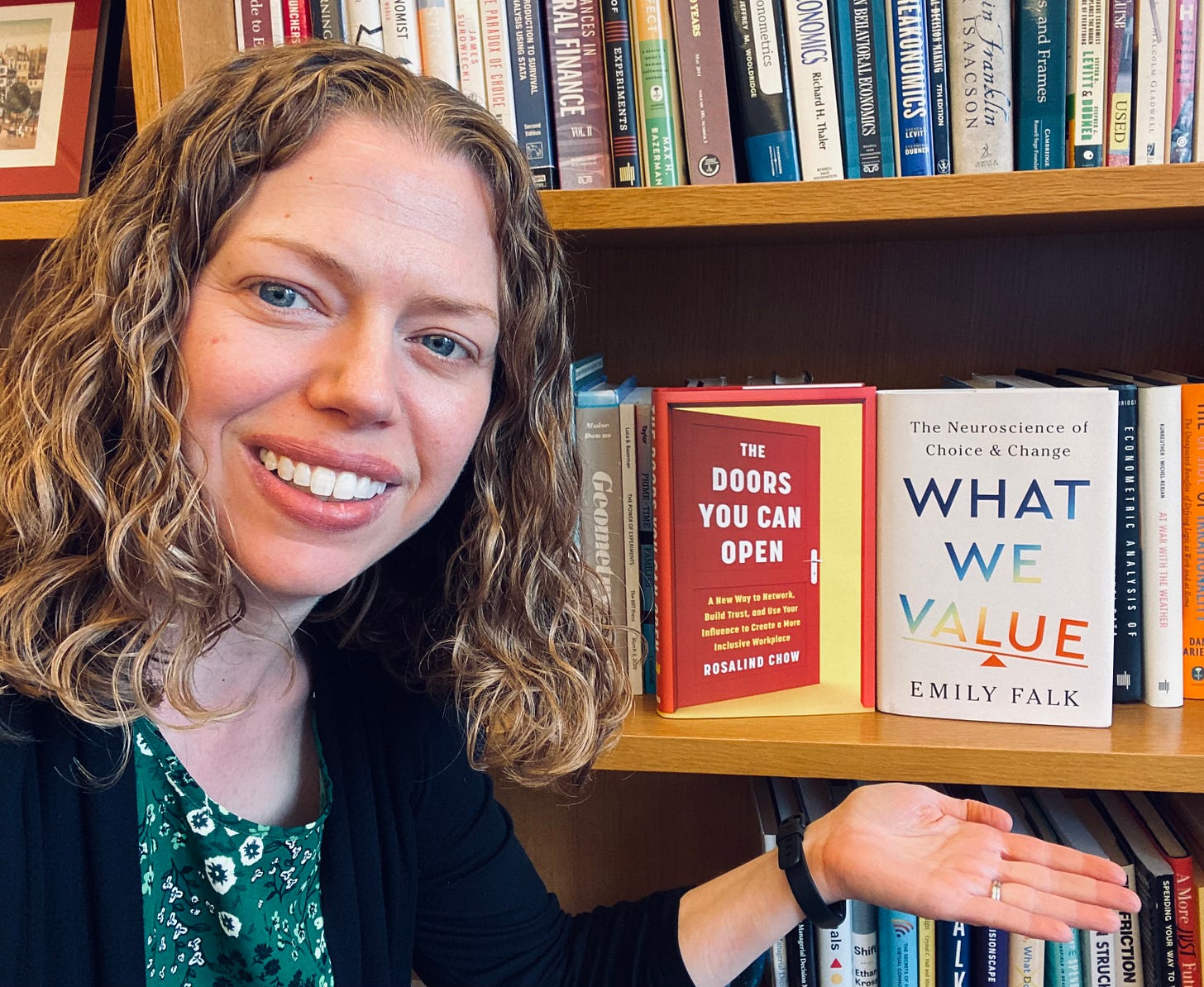

What We Value: Penn neuroscientist Emily Falk weaves together stories and science to explain how our brains make choices in this captivating new book for anyone who wants to learn and grow.

The Doors You Can Open: In her new book, Carnegie Mellon psychologist Rosalind Chow harnesses cutting edge research to suggest better ways to network, build trust, and foster inclusion.

Q&A: How You Imagine Likely and Unlikely Events

In this Q&A from Choiceology, UCLA Professor and behavioral scientist Craig Fox discusses his research exploring the way we think about low-probability events and how to make better choices in an uncertain world.

Me: Craig, can you start by describing the way people think about very high and very low probability outcomes?

Craig: Well, psychologically, the impact of probability isn’t linear. For instance, if I was selling all 100 tickets to a raffle for a trip to Hawaii, most people would pay more for their first ticket than for a 31st ticket if they already had 30. We're sensitive to the difference between ‘not going to get it’ and ‘might get it.’ We're also very sensitive to the difference between ‘probably going to get it’ and ‘certainly going to get it,’ so most people would pay even more for the 100th ticket to lock in that prize.

Me: So, what you're saying is that there are 100 tickets available and if I buy all 100, then I have a 100% chance of winning. And even if I don’t buy them all, the more tickets I buy, the more likely I am to win, so I value that first ticket the most.

Craig: Yeah. Psychologically, there's diminishing sensitivity to changes in probability around these two natural boundaries of impossible and certain. But we're not so sensitive to the difference between a 30% chance and a 31% chance. What that means is we tend to overweight low-probability events and underweight moderate-to-high probability events. People will pay a premium to enter some state lottery where they have a really tiny chance, because it's a lot more than no chance at all.

Me: That was a great description of the way we think about probabilities. Could you tell us why our minds work this way?

Craig: One idea that emerged from a string of studies was that it might be about attention.

Suppose you go to the doctor, and you have some sort of test, and the doctor says, "I don't like what I'm seeing in this image, Katy. I think it could be cancer." You're kind of freaking out! But the doctor says, "Don't worry. The probability is maybe 10%. We’ll do another test, take a biopsy, and we’ll call you next week." How would you feel about that?

Me: I wouldn't sleep for a week.

Craig: You wouldn't sleep for a week because never mind that it's a remote possibility—a 10% chance of having a deadly disease sounds incredibly frightening. That's where your mind is going. Your attention is shifting between two outcomes. I could die. I could live. I could die. I could live.

But what you don't do is simulate in your head getting ten calls from the doctor at the end of the week: (1) Good news. (2) Good news. (3) Good news. (4) Good news. (5) Good news. (6) Good news. (7) Good news. (8) Good news. (9) Good news. (10) Bad news. That's what 10% is. And that simulation I just did for you there is the basis of the things that we did in the experiments.

We gave people descriptions of events like a 10% chance of winning a prize or a 10% chance of some policy outcome, and we compared that to people's responses when you actually sampled the experience for them, like I did for you.

When we direct people's attention to the outcomes in proportion to their actual probabilities, what we find is that people weigh the probabilities in a more accurate, linear way. So they really subjectively “get” the difference between a 10% and a 90% probability in a way that they don't when you just describe it to them.

Me: So basically, just to summarize, when we think about why people overweight low probability events, the evidence suggests that it's because we don’t think in categories that are fine-grained enough to allow us to really appreciate an unlikely event. And we can correct that by giving people an accurate sample of what that low probability is like. And then once they've experienced those low probabilities, they react to them more rationally.

Craig: Yeah, exactly. We didn't evolve in a context where we use probabilities, but modern society requires it. We get weather forecasts in the form of probabilities and other kinds of information in a probabilistic way, but our minds have a hard time getting around those remote probabilities. We can calculate expected value if we've had a class in it, but to really feel it is difficult. And so, translating it into a more natural experience is one way of helping to overcome that, so our minds can kind of get around it by pushing our attention to the outcomes in proportion to their actual probability of occurrence.

Me: Craig, is there anything you do differently in your life because you understand this?

Craig: Yeah. Everything we’ve talked about leads to the conclusion that for most of the choices we make in life of small to moderate consequence, we should be risk neutral. So, I try to be risk neutral where I can. I try to self-insure for small things. Like, I have very large deductibles on my insurance, I decline the extra coverages, and so forth, recognizing that occasionally I'm going to lose. But overall, over the larger collection of experiences that I have in life, I'm going to come out ahead.

Me: To clarify, for large things, you would generally advise buying insurance, right? If you’re the primary breadwinner for your family, for instance, life insurance is a good idea, as is home insurance. But I think you're talking about the smaller risks.

Craig: That's right. Absolutely right. For the small to moderate things that we face, I try to shut off that little emotional voice in my head that says, ‘Danger, danger, danger.’ When I recognize that I'm overweighting an outcome with very low probability.

Me: Like riding on a plane and being nervous?

Craig: Yeah, that's a good example, especially, of course, after 9/11 when we were all a little bit more scared and attuned to the possibility of terrorism. We tend to overweight those probabilities and especially ones that are emotional like terrorism and the threat to our mortality. So, when I'm in situations like that, I try to think ‘OK, what's the actual frequency of these things happening on planes?’ And gosh, that's incredibly rare and probably isn't going to happen, and I'm not going to let myself overweight that in my decision of whether to fly.

It certainly is very human to be afraid if you're told that there's a low probability of some horrible thing happening to you. But also, in terms of the decisions you make, try to discipline yourself to go by the odds a little bit more, to calculate the expected values a little bit more, at least for the decisions we make in daily life. Learn to stop worrying and embrace uncertainty.

Me: Craig, thank you so much for taking the time to talk to me today.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

To learn more about Craig’s work, you can listen to this episode of Choiceology, where we dig into the way people think about probabilities or visit his website.

That’s all for this month’s newsletter. See you in May!

Katy Milkman, PhD

Professor at Wharton, Host of Choiceology, an original podcast from Charles Schwab, and International Bestselling Author of How to Change

P.S. Join my community of over 100,000 followers on social media, where I share ideas, research, and more: LinkedIn / Twitter / Instagram / BlueSky / Threads

Fascinating!

It sounds like the audio on Substack is generated by AI. It’s your voice cloned. Which AI service is it?

Dear Katy, I always await your material which I like to call a digest more interesting than Reader's Digest. Your advices suggestions and mantras are always superb and fantatic including intervieing

and books etc. Keep up doing it with same entusiasm dedication and concentration. Kuodos with love and huge hugs as a reward.