A surprising way your current mood can shape your future

UCLA Professor and behavioral economist Kareem Haggag explains attribution bias and why it matters

We’re just two months into 2025, and it’s already been a rollercoaster. Watching my hometown football team dominate the Super Bowl (go Birds!) was a high. But seeing my government drastically scale back support for science and research universities? That was a low. After yelling at screens in excitement and frustration, I’ve wondered what toll my strong emotions may be taking on the way I judge everyday experiences. Research shows our emotional states – be they states of elation, disappointment, hunger, or exhaustion – can have big spillover effects. Emotions don’t just affect us in the moment; they can also distort our future judgments in ways we may not realize.

If you’ve heard the expression “don’t shoot the messenger” (which can apparently be credited to Sophocles), then you’re already familiar with the idea of emotion attribution errors. In ancient times, angry rulers literally killed messengers for delivering bad news, even when they had nothing to do with it. That’s because the anger these messengers incited when sharing bad news (of, say, defeat on the battlefield) spilled over and unfairly tainted the way they were viewed. In this month’s Q&A, you’ll learn how your emotional state when eating a meal, taking a class or trying a new workout can spill over to affect the attributions you’ll make about that experience in the future (sometimes with life-altering consequences).

But before we dive in, here are a few listens and reads I think you might enjoy…

This Month’s Recommended Listens and Reads

How to Make a Good Impression Online: Professor Andrew Brodsky’s evidence-based op-ed in the Wall Street Journal offers invaluable guidance on how we can all make a better impression on Zoom and over email.

What to Do After Accomplishing Your Goal: This New York Times piece offers tips on how to harness the natural comedown you may feel after nailing a goal, some of which were provided by yours truly.

Why Streaks Keep Us Hooked: The New York Times covered terrific research by Professors Jackie Silverman and Alix Barash showing that we fear breaking streaks because they feel like possessions we don’t want to lose, and this can motivate us to stay on track when games and apps emphasize our streaks of achievement.

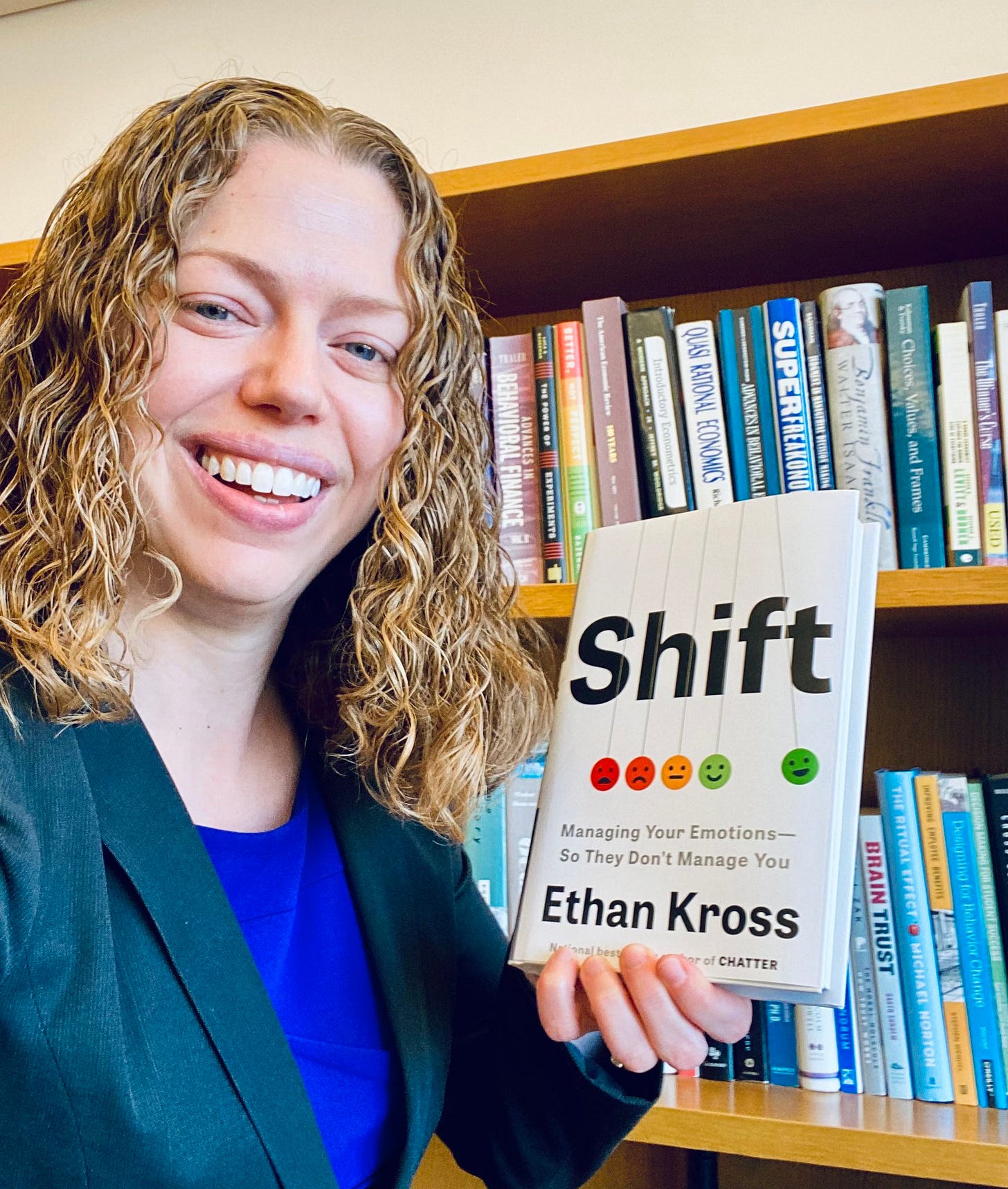

Ethan Kross is a world-renowned expert on emotions and how to regulate them, and he released a new book earlier this month called SHIFT: Managing Your Emotions So They Don’t Manage You, which became an instant bestseller. I highly recommend SHIFT as well as Ethan’s fabulous first book, CHATTER: The Voice in Our Head, Why It Matters, and How to Harness It.

Q&A: Misattributions Matter

In this Q&A from Choiceology, UCLA Professor of Behavioral Economics Kareem Haggag discusses his research showing that people make predictable misattributions when recalling past experiences and explains why this bias matters.

Me: Let’s start off with a definition: what is attribution bias?

Kareem: The basic idea is that when judging the value of a good, people tend to be overly influenced by the state in which they previously consumed it. States refer to things like our hunger, thirst, fatigue, or even what the weather is like. The amount of enjoyment we get out of consuming a product or experience often depends on what state we happen to be in. For example, food is tastier when you're hungry.

However, a large body of research in psychology and behavioral economics suggests that we fail to appreciate the extent to which our preferences change with our states, and that can lead to misattributions.

So, imagine you went to a new restaurant after working up a large appetite. You're probably going to enjoy the food more than if you went when you were less hungry. But later, when you reflect on that experience, you may fail to realize that you liked the food so much because you were so hungry. So, when you recommend the restaurant to friends or you think about going back, you may overrate the restaurant or go back and be disappointed.

Me: I know you have a really interesting study that shows that attribution bias can even change what majors college students are interested in pursuing. Can you describe it?

Kareem: In that project we explored whether students might be making these sorts of misattributions during intro classes where they often get a first taste of a subject. Our hypothesis was that students who were assigned to an early morning section of a class or to multiple back-to-back classes might mix up how tired they are with how much they like the subject—thus leading them to be less likely to choose the subject as their major.

This was tricky to study because in many colleges, students can choose when to take their classes, and that's why we decided to do it at West Point. Because at West Point, students are randomly allocated to class times across a standardized core curriculum, which allows us to compare students assigned to different timings for their courses without worrying about, for example, them choosing to put their least favorite classes in the morning. We found that students randomly assigned to the 7:30 a.m. section are about 10% less likely to choose the corresponding major than a student who takes that class later in the day. So, if you're assigned to 7:30 a.m. Chem 101, you're about 10% less likely to become a chemistry major.

Me: I love this finding. It’s such an interesting demonstration of what a big impact a seemingly small bias can have on our lives. It can literally shape the profession we pick. And it brings me to my next question: why are we so bad at correctly adjusting our beliefs when our experience is shaped by being hot or encountering a rainy day or being sleep deprived?

Kareem: I think this relates to a broader psychology on anchoring and adjustment. We anchor on what our experience is in the moment, and it’s very difficult to fully parse it, even when the state is very salient. I find this a lot in my own life. For example, when I started working on this project, it was, I think, either right before or during the month of Ramadan, which is the month in which Muslims fast. And I had this sort of common experience of fasting all day. And then, particularly in grad school, we would go out to a new restaurant or to a friend's place, and they'd make a new dish, and it's always the most amazing meal after being hungry all day. But when I go back to one of these amazing restaurants after Ramadan is over, I'm invariably disappointed by the quality of the food.

Me: That's a fascinating example. Did that motivate this work?

Kareem: To some extent, yeah. It came up as we were brainstorming ideas.

Me: That’s a really nice illustration of how important it is that researchers have different backgrounds and experiences to motivate diverse research questions.

I’m curious what you do differently now that you know attribution bias?

Kareem: I would say that if it’s easy, I reflect on my underlying state. So, if I met someone for the first time and I had a bad headache, I might later consider how that could have played a role in my judgment of how engaging the conversation was. Or if I knew that I sampled something when I wasn’t in the best state for it, I try to go out and sample it again before deciding about it or giving a recommendation. So, if I try a restaurant when I’m incredibly hungry, maybe I try it again in a regular state of hunger before singing its praises to everybody.

For example, I recently went backpacking in Yosemite for the first time. I'm not a backpacker. I'm not a regular hiker. But I went with some friends who knew what they were doing, and we got these dehydrated meals. Pretty far into the hike we boiled some water to rehydrate the meal kits. And it was the most amazing meal I've ever had, this chicken and dumplings meal. It crept into my mind for a moment that maybe I should get some of these dehydrated meals and keep them around the house for when I don't have other food. But I think that's probably a misattribution. They probably don't taste as good without having done a strenuous hike. That just, again, illustrates how hard it is to know, because I've never had one of these meals when I wasn't so hungry.

From a more administrative perspective, I’m now a little bit more sensitive to the role of timing. So, if it's possible for me to choose not to teach a class early in the morning, not only for my own sake but also for the students, I perhaps try to take a later time of day.

Me: What advice would you give to others who want to avoid making this kind of attribution mistake?

Kareem: My advice would be to test something new multiple times while you’re in different states. For example, let's say you're trying some new exercise at the gym. If you put it at the end of your workout, you might misattribute how difficult or enjoyable it is to how tired you are at the end of that workout. And so, I would encourage you, the next time you go to the gym, to try the exercise at the beginning of your workout just to calibrate how much of a role your fatigue might have played in that evaluation.

Me: I love that. So more generally, we should try to sample new experiences in different states before forming strong judgments of those experiences. Kareem, this has been fascinating, and I really appreciate it. Thank you.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

To learn more about Kareem’s work, listen to the episode of Choiceology where we dig into attribution bias or check out his terrific paper in the Journal of Public Economics on how this bias can contort the majors people choose in college.

That’s all for this month’s newsletter. See you in March!

Katy Milkman, PhD

Professor at Wharton, Host of Choiceology, an original podcast from Charles Schwab, and International Bestselling Author of How to Change

P.S. Join my community of ~100,000 followers on social media, where I share ideas, research, and more: LinkedIn / Twitter / Instagram / BlueSky / Threads