Why we should use checklists far more often than we do.

One day in late September, I forgot to put my son’s water bottle in his backpack alongside his lunch, snack, and backup masks. As soon as I realized what I’d done, I was stricken with panic that he’d be desperately thirsty all day but too shy to ask a teacher for something to drink. Determined not to make a mistake like that ever again, I printed a checklist of the items that belong in my son’s backpack and placed it on the refrigerator. I haven’t made another mistake since. My improved track record might just be due to luck or my heightened attentiveness after a goof, but I’m betting the checklist has helped.

This month, I’ll share a conversation with Northwestern University Professor Kirabo Jackson, whose research on checklists suggests we should rely on them far more than we do.

But first, a few recommended listens and reads...

Recommended Listens and Reads

Not Just Another Statistic: In this episode of Choiceology, my Wharton colleague, Professor Deborah Small, explains why we’re so motivated to help individuals in need when we hear their personal stories, and less moved to help large groups.

Using Nudges In Your Personal Life: If you're curious about how nudges can help with daily life (and not just public policy), check out this CNN Q&A in which I discuss using nudges to change your own behavior or to help people you love change theirs.

I recommend perusing two new books that are out this month:

The Elements of Choice from Columbia Business School’s Eric Johnson explains why the way we decide matters.

The Human Element from Kellogg School of Management’s Loran Nordgren and David Schontal takes a deep dive into the science of idea generation and innovation.

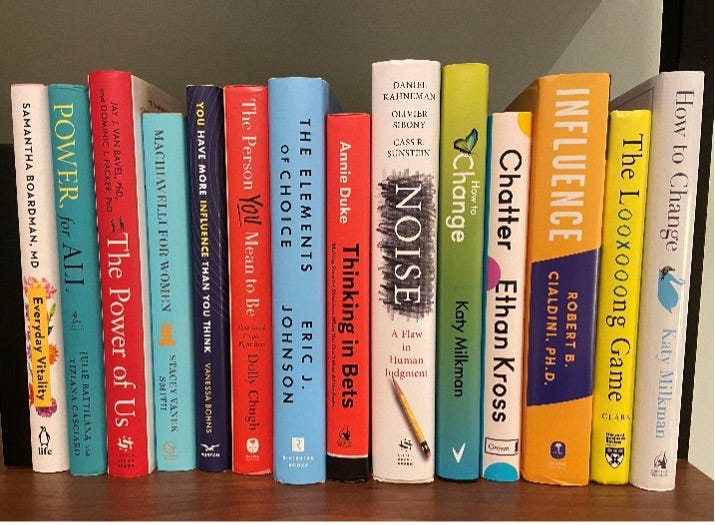

For a few bonus recommendations, here’s a snapshot of what’s currently on my bookshelf…

Q&A: Checklists

In this Q&A from Choiceology with economist and Northwestern University Professor Kirabo Jackson, we talk about Kirabo’s research on the power of checklists to improve outcomes.

Me: Kirabo, can you share your research about how checklists can improve our decisions?

Kirabo: Sure. My co-author Henry Schneider and I ran a very small experiment in auto mechanic shops. Mechanics have pretty complicated jobs—a car comes in, you have to identify a problem and fix the problem. So we thought perhaps a checklist would be a helpful way to improve the productivity of mechanics. Checklists can provide a sort of external memory device to help people stay on track so they don't miss steps. Checklists also provide some external accountability. Everyone has to go through the checklist. It ensures that whoever's doing the task is doing it properly.

We provided checklists to auto shop owners and asked them to use them in three or four of their shops. It was a very standard auto mechanic checklist that listed things like: lift up the hood, check the oil, check the lights, check the brakes. Basically, it goes through all the components of the car that a mechanic would want to look at to identify any problems.

For three weeks, the mechanics used these checklists and we looked at their data to see what happened.

Me: And what did you find?

Kirabo: When we provided the checklists—and I should be very clear that the owners were instructed to make sure mechanics were filling them out—total revenues went up by about 25 percent.

A cool component of the paper was that we were able to use data from before the experiment, where some mechanics were paid by commission. And for some of the mechanics, their commission went up from say 10-11 percent to 11-12 percent. We were able to benchmark this increase in revenue against what you might expect to see based on an increase in performance-based pay. We found that having these checklists increased revenue by about the same amount as a roughly 1.5 percentage point increase in the mechanics’ commission, which is a pretty large effect. And it's relatively cheap.

Me: Wow! Why do you think checklists aren't used much more widely, if they’re so useful?

Kirabo: Essentially, there’s a moral hazard, which in economic terms mean that an individual bears the cost of some action but the benefits accrue to somebody else. In this context, the mechanic is the one who has to exert the effort to go through the checklist. Maybe it’s actually a pain in the butt, and they're not getting paid additional money. And even though some mechanics saw an increase in commissions, all of the benefits of this more thorough inspection are essentially going to the owners.

After the three-week period, we left additional checklists with the shops and told the owners, "You no longer have to look at them. We're just going to see if they're being used." And when the owners weren’t collecting the checklists, no one was using them.

So ideally what you'd want to do is compensate the workers for the additional effort that the checklist entails.

Me: That’s really interesting. When and why are checklists most valuable, do you think?

Kirabo: When things are complicated, that’s when people forget things. The other time checklists could be really valuable is when things have to happen step-by-step in a multi-step process. It can be difficult to keep track of a whole bunch of different steps unless you write things down and make sure you're staying on task. So, I think multi-step situations that are complex are exactly when you're going to want to use a checklist.

Many jobs have a piece that’s complicated or diagnostic. By externalizing the keeping track of things, you can focus more of your effort on doing the things you need to do.

To learn more about the power of checklists, listen to the episode of Choiceology where we dig into the topic or read Atul Gawande's wonderful book The Checklist Manifesto.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

That’s all for this month’s newsletter. See you in November!

Katy Milkman, PhD

Professor at Wharton, Host of Choiceology, an original podcast from Charles Schwab, and Bestselling Author of How to Change