a bias that confounded Aristotle

I hope you had a wonderful Valentine’s Day! As a sign of my love for you, dear subscriber, I’m sharing an interview with one of the greatest living social psychologists about a bias so fundamental that the word fundamental is in its name! I’ll cut to the chase quickly so you can learn about a logical error profound enough to confound Aristotle. But first I have just a few recommended listens and reads to share.

This Month’s Recommended Listens and Reads

Science Can Help You Break Bad Habits: This Newsweek cover story dives into the neuroscience of habits before sharing practical tips for breaking the habits you hate.

The Bad with the Good: In this recent Choiceology episode, I interviewed Uzma Khan about why recognizing you’ll have a chance to make the same decision repeatedly in the future—about what to eat for lunch, what movie to watch, etc.—makes you more likely to select indulgent choices now.

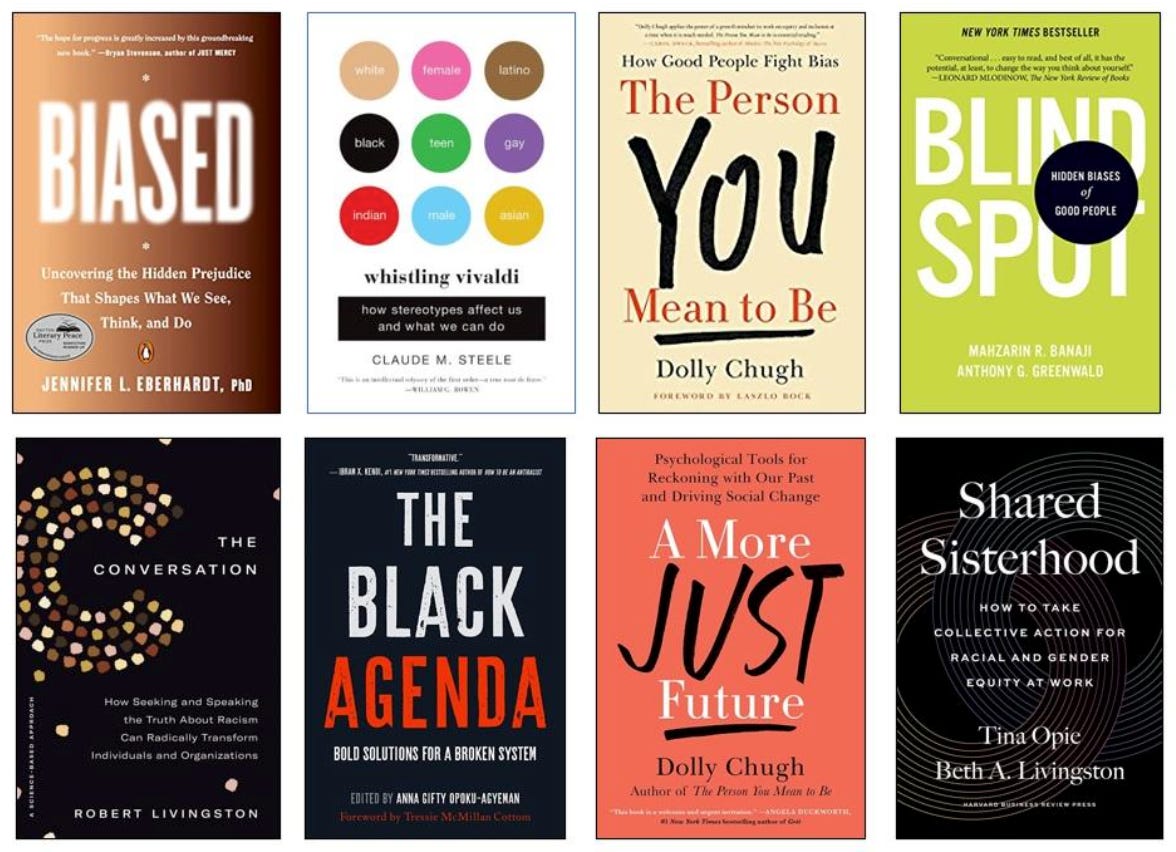

Behavioral Science Books to Read During Black History Month: These aren’t Black history books, but they’re terrific books that will help you understand what behavioral scientists have learned about race and racism and how you can combat it.

Q&A: The Fundamental Attribution Error

In this Q&A from Choiceology, University of Michigan Professor Richard Nisbett describes his research on the fundamental attribution error, which leads us to misjudge people (and objects) at an alarming rate.

Me: What is the fundamental attribution error?

Richard: The fundamental attribution error is our tendency to attribute causality to dispositions of the actor and to slight situational constraints and opportunities. So basically, when you and I are having a conversation, I'm largely unaware of the broad range of stimuli to which you're responding. And if you seem very pleasant, I'm sure you’re a very pleasant person. But it's limited evidence. I've ignored your situation.

Me: Could you describe a favorite research study that demonstrates this fundamental attribution error?

Richard: Well, let me give you two examples. The first is 2,500 years old. It's Aristotle's physics. Aristotle would tell you that a stone sinks when it drops into water because it has the property of gravity. But there's this problem, of course, which is that if you drop a piece of wood in the water, it floats. No problem for Aristotle, that's because the wood has the property of levity.

Now, of course there's no such property and gravity isn’t inherent in the object. It's inherent in the relationship between the object and something else, for example, earth.

When I was at Yale, we did an experiment where we contacted students at Yale, and said there are a number of well-heeled visitors who we're hoping to get their contributions to the university and if you would be willing to show them around for a couple of hours, we could pay you. We could pay you $10 an hour for a couple hours of work, and to others we said we could pay you $30 an hour. Now, some of them said yes and some of them said no, but of course they were substantially more likely to say yes for $30 an hour.

Meanwhile, we had videotaped these interactions and we showed them to people and asked them a few questions about what they had seen. How likely did they think it would be that the person they just saw would be willing to volunteer for the Red Cross for a half day’s work? When people made these judgements, they were almost completely unresponsive to the amount of money that was offered to the student. If the student said yes, and had been offered $30, the judge was no more likely to assume that she would volunteer for the Red Cross than if she had only been offered $10 and agreed to do it. So that's fairly spectacular because the amount of money offered, of course, exerted a big influence on whether people volunteered or not.

Me: That study is so fascinating. Essentially, people attribute all of the generosity they see to the person and not whether they were offered $10 or $30 to exhibit generosity. Why is it that we infer personality is the root cause of so much behavior that's actually determined by the situation?

Richard: There's a strong temptation to say it's something about the object—which could be a stone or a person—that caused them to do that.

The situation is often invisible to me. I don't know what kind of morning you had today. I don't know anyone that you spoke to before, who might've told you something wonderful or something upsetting. I can't know that. So a lot of the situational factors that influence our behavior are simply not visible to the observer. That's a big part of it.

But as our study at Yale shows, we can be awfully obtuse, even when it's rubbed in our noses. So, there really is something very deeply flawed about our ability to incorporate situational information into our judgment about why people do what they do.

Me: Why should we be concerned about this mistake?

Richard: Well, we're constantly making errors as a consequence of the initial error. I mean, I decide somebody's nice based on inadequate evidence, and then I ask him to do me a favor and he doesn't because actually, he's not so nice. We make snap judgements about people on a limited amount of information. And when that's the case, we're going to make errors in our interaction with that person again because we assumed that the reason for some particular behavior was the disposition of the person, their personality trait, or their skill, rather than a response to this specific situation.

Me: For your average person, what do you think their key takeaway should be from learning about this?

Richard: Get more evidence. I mean don't assume that a single encounter or a single anecdote about the person is terribly informative. We don't fully understand the concept of a law of large numbers, which basically says, in its simplest form, more evidence is better than less evidence.

Me: That’s an excellent takeaway. Thank you very much.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

To learn more about research on the fundamental attribution error, listen to the episode of Choiceology where we dig into the topic or pick up a copy of Richard Nisbett’s classic book with Lee Ross, The Person and the Situation: Perspectives of Social Psychology.

That’s all for this month’s newsletter. See you in March!

Katy Milkman, PhD

Professor at Wharton, Host of Choiceology, an original podcast from Charles Schwab, and Bestselling Author of How to Change

P.S. If you know someone who you think might enjoy this newsletter, consider encouraging them to subscribe!

P.P.S. Interested in working with me and my research team at the Penn-Wharton Behavior Change for Good Initiative? We’re hiring a Research Project Manager. You can learn more about the opening and/or apply here.