Why Arbitrary Categories Matter

I’m celebrating a round number birthday this month, and I can’t stop thinking about categorization. In honor of entering a new decade (40s here I come), I’m sharing an interview with Nobel laureate Richard Thaler on the topic of categorization, or what he calls “mental accounting.” It turns out that the somewhat arbitrary ways we categorize money and time have all sorts of fascinating implications.

Sharing this interview as I approach a meaningful birthday feels doubly appropriate since it was a book of essays by Richard Thaler (The Winner’s Curse) that led me to drop what I was doing and become a behavioral scientist.

Before I share my conversation with Richard, here are this month’s recommended listens and reads…

Recommended Reads

Disgust Matters More than You Think: This magnificent article explores the science of disgust and features one of my all-time favorite Penn colleagues - the brilliant psychologist, Paul Rozin.

Is 2022 the Year for Pragmatism?: This Atlantic essay argues the answer is “yes” and shares a few insights from my research along the way.

An Entrepreneur’s Book Guide for 2022: What’s not to love about this reading list from Inc., which includes titles ranging from How to Change to Will.

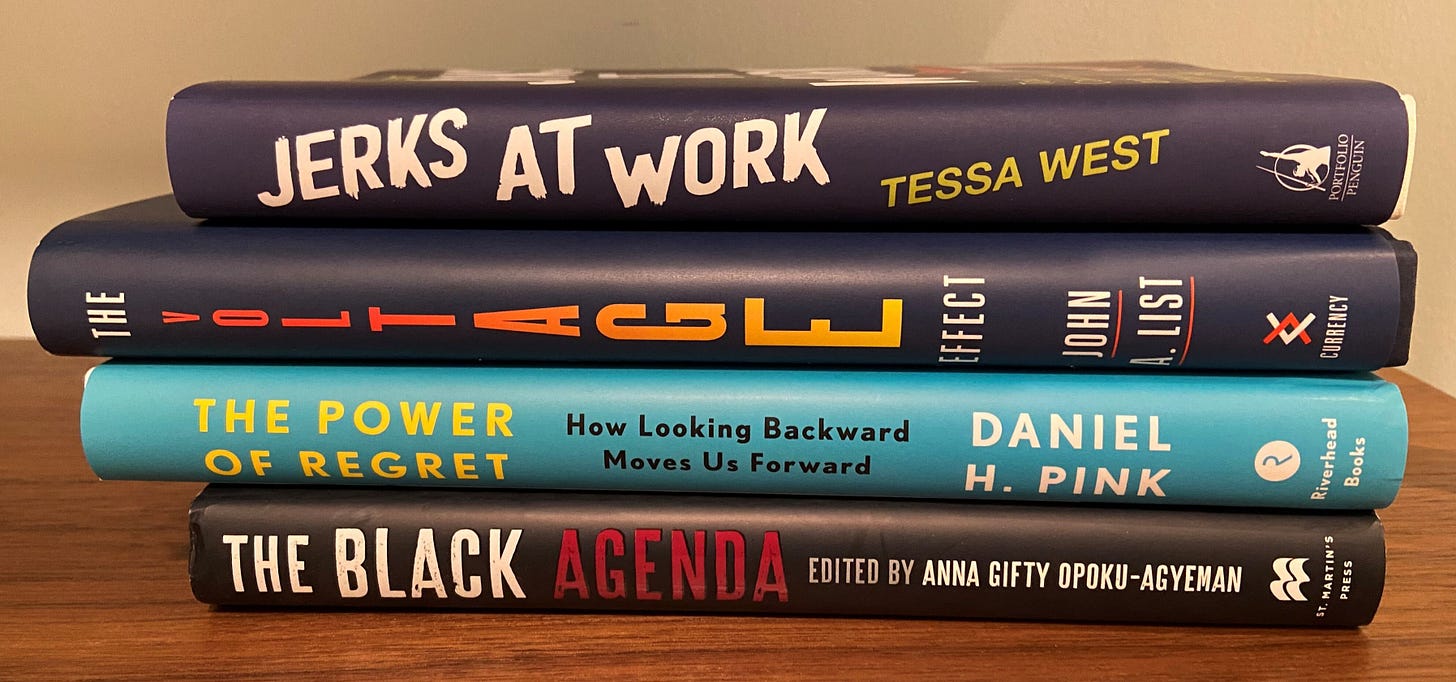

Finally, here are a few new books on my shelf that I’m particularly excited to suggest to you:

Q&A: Mental Accounting

This Q&A from Choiceology with Nobel prize-winning economist and University of Chicago Professor Richard Thaler covers mental accounting, self-control, and how they relate.

Me: I want to talk about mental accounting, or our tendency to treat time, money and other resources in a way that economists tend to think is quite peculiar. We put time and money into categories and then act like we can’t make transfers across those categories. Could you explain?

Richard: There's a clip I always show in my class. A discussion between Gene Hackman and Dustin Hoffman. Gene Hackman is telling this story about when they were both starving young actors. He goes over to Dustin Hoffman's house and Hoffman says he needs a loan. Hackman says, "No, you don't need a loan. I saw in your kitchen, there are all these mason jars, and they all have money in them.” Hoffman says, "Yeah, but the jar labeled, 'Food,' doesn't have any money in it. I can't take the money out of the utilities jar and spend it on food.”

When I was first doing research on this, I hired an RA to talk to lower income and lower-middle income families about how they do their budgeting. These talks very much confirmed the impression that people were forming these mental accounts, either explicitly or implicitly, and then using that as a way of keeping their finances in line.

Me: How does this relate to what economics says we should do?

Richard: Suppose we think about the model we would teach if either of us was stuck teaching basic microeconomics. Somebody goes into the grocery store where there are thousands of items and then solves for the optimal portfolio of groceries that will maximize their utility subject to some budget constraint. Of course, it's preposterous that anybody would do that. Even those of us with PhDs in economics would never think about doing that, and if you tried you would starve to death, because the problem is too hard. We have to simplify.

One way of simplifying is to put stuff into categories. Then the relation between mental accounting and regular financial accounting — they're really quite the same. My colleagues, Neil Mahoney and Jeff Liebman, have a recent paper showing how government budgets that expire at the end of the year create all kinds of weird behavior. You see a big spike in spending on the west coast on the last day of the fiscal year, because people didn't manage to get it all spent on the east coast. They have 100 grand left at midnight on east coast time, which is 9pm west coast time, so they call their friends in California and say, "Can you figure out what to do with it?"

On the consumer side, there's a paper by Ethan Soule that shows that if you've gone out to dinner in the middle of the week, maybe because a friend came in from out of town, and you don't normally go out for a fancy dinner in the middle of the week, then you're less likely to do that on the weekend because your out-to-dinner budget has already been spent. We see all kinds of silly decisions made by both individuals and consumers because they're keeping these mental accounts.

Me: Why do you think people mentally separate their money into different categories?

Richard: They're for self-control reasons.

Me: Ah yes. Self-control. Will you tell the story of what first got you interested in studying self-control?

It goes back to my graduate student days. I invited a bunch of economics graduate students over for dinner. As our meal was cooking in the oven, we were having an adult beverage and I put out a large bowl of cashews that we started nibbling on. After five or 10 minutes I realized that we were rapidly devouring these cashews and so I rudely grabbed the bowl and hid them in the kitchen.

I came back and everybody was happy. "Thank god you got rid of those nuts. We were going to eat them all." Then, since it was a group of economics graduate students, we immediately started analyzing what had happened. We realized we weren’t allowed to be happy because the first principle of economics is that more choices are better than less, and before we had the choice of eating nuts or not. Now we didn't. We were worse off but happy. How could that be?

That got onto my list of funny behavior I should think about. It's of course an illustration of a self-control problem. We knew if the nuts were there, we would eat more than we thought was best. But the idea of eating more than you think is best is something economists don't really permit. This is one of these parts of economics that never gets written down. Nowhere in any textbook does it say that there are no self-control problems. Instead it says people choose to maximize their utility.

There's the fancy term, “consumer sovereignty,” which means we do better at choosing than anyone else could. But in fact, we often don’t choose as well as we could in the sense that we make choices we know we'll regret later. That we would have eaten more of those nuts than we would have chosen to eat was a small example. My mistake was filling the bowl too much.

The realization that people struggle with self-control has led to decades of research by me and others on how to help people save for retirement. It basically amounts to taking some part of the pay package and hiding it in the kitchen where we can't spend it.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

To learn more about Richard’s research on mental accounting, listen to the episode of Choiceology where we dig into the topic or read Richard’s book Misbehaving.

That’s all for this month’s newsletter. See you in March!

Katy Milkman, PhD

Professor at Wharton, Host of Choiceology, an original podcast from Charles Schwab, and Bestselling Author of How to Change